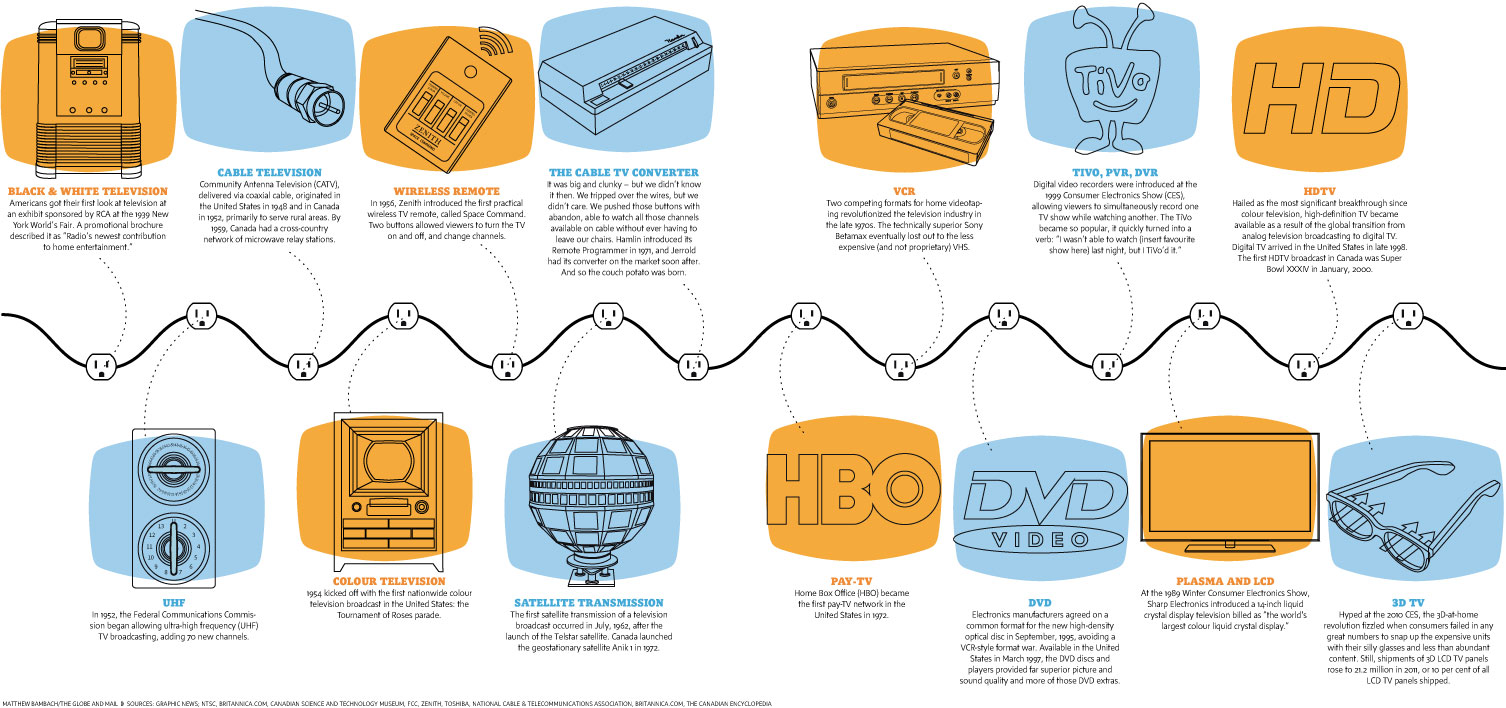

Televisions used to be big and clunky, just like computers and cell phones were when they first hit the shelves. Nowadays it seems the thinner the television set is, the better. Most of us also look for crisper, clearer, and brighter resolution in our TVs, which has ultimately changed the way televisions are made.

Of course this all didn’t happen overnight. Take a look at this infographic to see how the television has evolved throughout the years.

This infographic from Visual.ly comes to us via Albuquerque Car Dealerships and explores “The Infographic Life Cycle”. Click to enlarge.

Hat Tips: Alanta Dodge